There’s been a lot of discussion lately about the “troubled teen industry,” a multi-million dollar sector of residential care that promises to “fix” kids for a fee. The most notable voice on this topic is Paris Hilton, whose parents put her in a residential program as a child and now, at age 43, talks openly about the inhumane treatment she experienced. She has dedicated her wealth and privilege to ensuring that no other kids endure what she did. The industry is very strong, though, so it’s been a fight.

Recently, congressional investigations resulted in a 136-page report titled Warehouses of Neglect: How Taxpayers Are Funding Systemic Abuse in Youth Residential Treatment Facilities. The report uncovered that the harms are inherent in the congregate care model, with rampant sexual and physical abuse, privacy violations, dehumanization, and insurance fraud (if those other things don’t bother you enough). The report predictably recommended more oversight, but also the need for more alternatives. Most families put their kids in these programs because they don’t know what else to do.

Sometimes the motives are murkier, though. Take the recent case of a wealthy white couple who adopted a 10-year-old Black child from Haiti. As he got older, he started doing typical teenager things. They sent him away to boarding schools and residential programs, eventually dumping him in a school in Jamaica where he and other kids reported abuse. When an advocate got the boy returned to the U.S., his adopters declined to let him to come home. He was put in foster care instead, and the adopters now face child maltreatment charges.

Families with fewer resources are persuaded by social services that surrendering older children to foster care is the only way to get the help they need. The issue has become so concerning that the Department of Health and Human Services commissioned a study on it. If you know anyone who might be interested in participating, here are the details:

Mathematica, an independent research firm, is conducting a study on behalf of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services about families that have had children enter foster care primarily to receive behavioral health or disability services, rather than because of maltreatment. As part of the study, Mathematica is conducting a virtual focus groups with parents and young adults (over 18 years old) that have lived experience with this type of case. Individuals will receive $55 for participating in the 1-hour focus group. If you are interested in participating in a focus group or if you have any questions about this study, please reach out to Betsy Keating (ekeating@mathematica-mpr.com) and Dani Rockman (DRockman@mathematica-mpr.com). If you’d prefer to talk via phone, please reach out to Betsy Keating at (312) 994-1014.

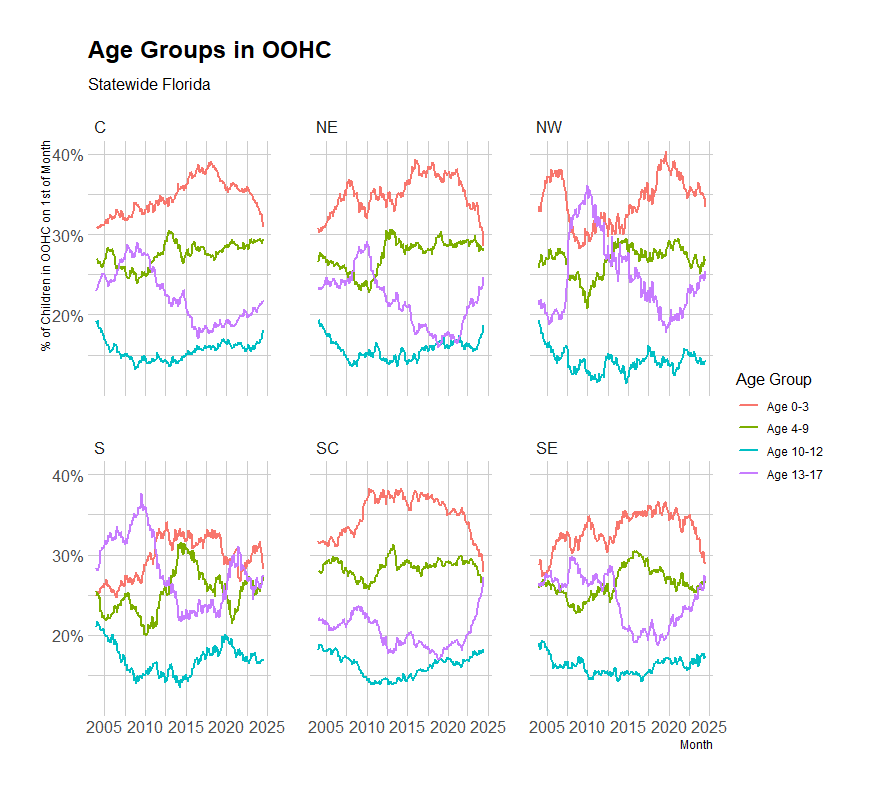

Florida’s System is Getting Older

The number of children that Florida’s DCF takes into custody has been declining, including for teenagers. In 2005, DCF took about 1,000 youth age 13-17 into custody each quarter; now, that number is closer to 300.

But, the number of babies and young children has been decreasing even faster, creating a demographic shift where teens are becoming a larger percentage of the out-of-home population. This has happened before, notably in the Northwest and Southern Regions in 2010, but this is the most significant change we’ve seen statewide.

Local systems will need to adapt to this change, starting with their mix of placements. Foster parents who are eager to care for a baby are rarely as willing to take in a teen, especially one with complex needs. Sometimes, teens are taken into custody because of their own issues rather than parental maltreatment, and unprepared foster parents and programs kick them out, repeatedly. In many cases, those teens might have been better off staying at home.

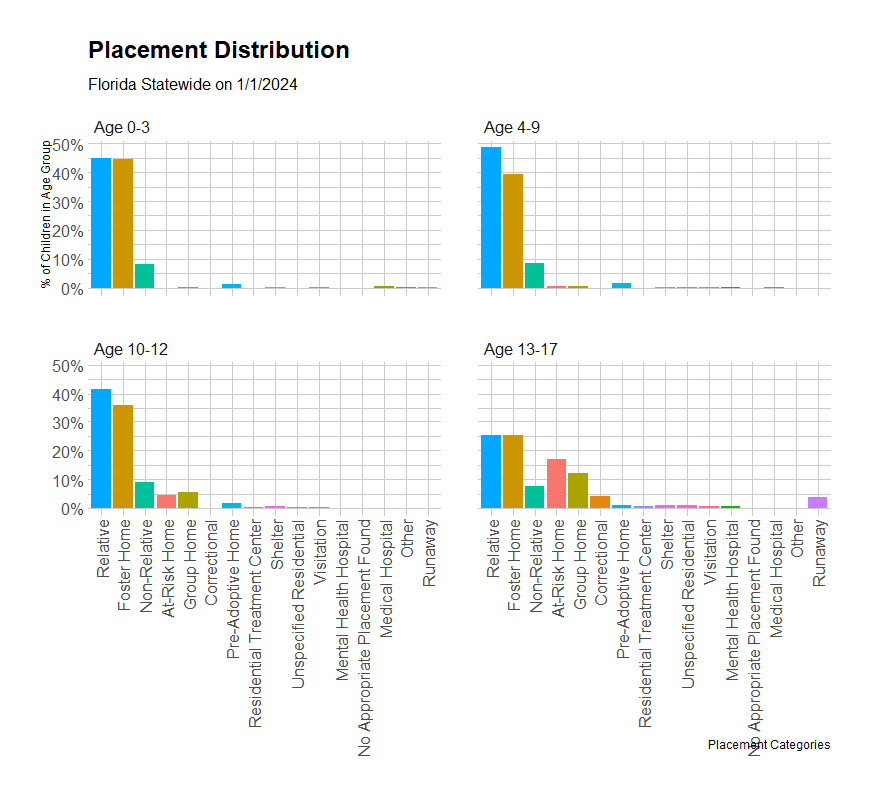

As of January 1, 2024, nearly 98% of children age 0-3 were in foster homes or with relatives or non-relatives, while only 58% of teens had family-like settings. Most of the remaining 1,800 teens were in congregate care, hospitals, or jails. About 4% of teens were on runaway status, about the same number were in jail, approximately 70 were in residential treatment centers (but DCF’s records on this are sometimes vague), and 25 were in mental health hospitals.

Another day I’ll write about the different experiences of those 1,800 kids compared to the 2,500 who were welcomed into family homes. The question is always: do older kids do better in congregate care? Even years after they leave, many of them emphatically say no.

so important. DCF is not only perpetuating but increasing the trauma for many of these teens. And having them arrested from the DCF offices while simultaneously depriving them of anything (meaningful or otherwise) to do or access to phones/belongings.